Please update your browser.

Stories

Training America’s Workforce: What’s Working in Three Different Cities

A conversation with three leaders working to guide America’s inner cities to well-paying jobs and set them on pathways to growth.

PARTICIPANTS

Dr. Donnie Hale Jr.

director of The Education Effect in Miami

Brenda Palms Barber

executive director of the North Lawndale Employment Network in Chicago

Kristen Blessman

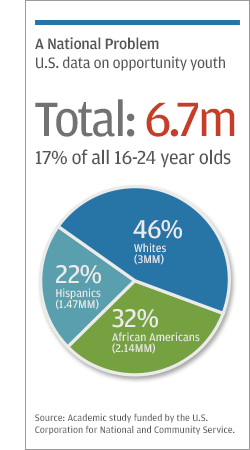

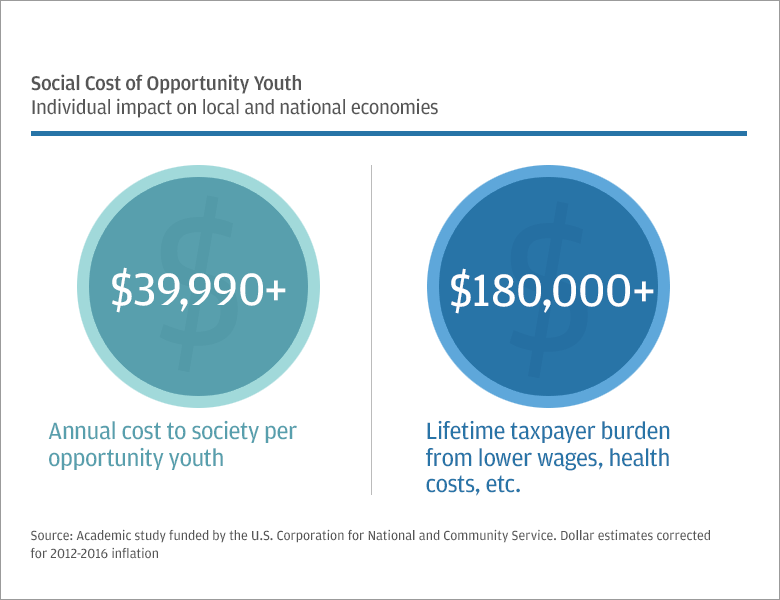

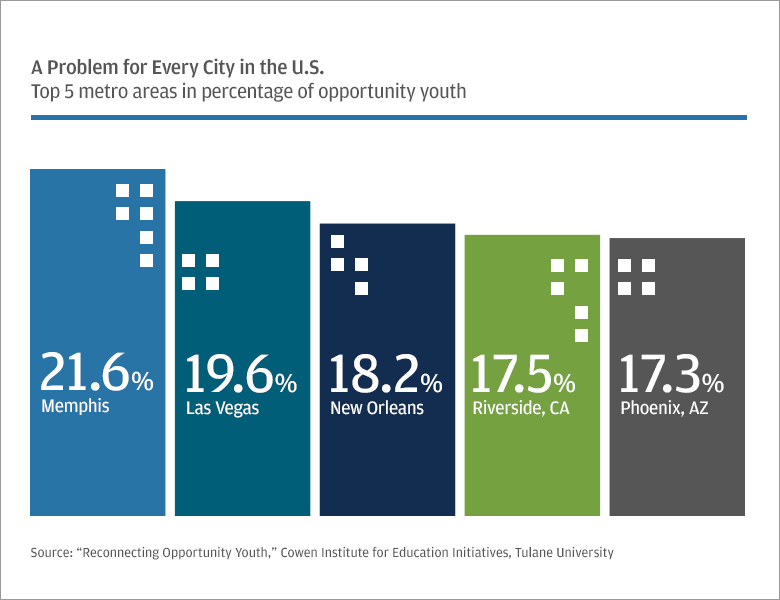

chief marketing officer of Goodwill Denver

Every American city has its own distinctive culture and charms, but at the heart of many of them lives a disturbing similarity—a large population of undereducated, unemployed young people. But efforts are underway across the country to prepare them for well-paying jobs around the country that are now in high demand: welding, health care, IT, and auto maintenance, for example. Such so-called middle-skills jobs don’t require a college degree, but they need more than a high school degree. This disconnect between training opportunities and open jobs stands between success and failure not only for them, their families, and their communities, but also for the stability and health of communities across the country.

To learn more about what is working on the ground, we brought together three people who have dedicated themselves to preparing people for careers: Brenda Palms Barber, executive director of the North Lawndale Employment Network in Chicago; Dr. Donnie Hale Jr., director of The Education Effect in Miami; and Kristen Blessman, chief marketing officer of Goodwill Denver. What follows is an edited transcript of their conversation with us—which quickly became a lively exchange with each other.

Atlantic Re:think: First, could you give us a sense of the people each of you is trying to reach and the problems you face?

Brenda Palms Barber: The North Lawndale Employment Network is located on the west side of Chicago in a community where the median income is about $18,000, at least 96 percent of the population is African-American, 57 percent of the adults have been in the criminal justice system, and the unemployment rate could be as high as 51 percent. We have a special focus on serving men and women returning from incarceration.

Kristen Blessman: At Goodwill Denver, we have a problem that I’m not sure everyone’s aware of: It’s called the Colorado paradox, where 37 percent of individuals here have at least a college degree, but we’re not educating our own community. We have a large influx of individuals moving here who are highly educated, but individuals growing up in our school system aren’t graduating. In Metro Denver urban schools, the graduation rate is about 47%. We’re trying to focus on opportunity youth between the ages of 16 and 24, trying to put them in middle-skill jobs and careers where they can grow.

Dr. Donnie Hale Jr.: The Education Effect also focuses on opportunity youth. We’re in three communities: Liberty City, Overtown, and Little Haiti. Liberty City is 95 percent black. One of the problems is that the youth who show promise end up leaving to go elsewhere. Once the others get to high school, they’re the “struggling youth”. Little Haiti’s high school has 750 students but they can hold 2,000. My staff is on-site daily in the public schools to help in places where the counselor-to-student ratio is 1 to 450.

AR: How do you approach problems this challenging?

Brenda: We serve roughly 3,000 people a year. A year and a half from now, it’ll probably be about 5,000. We have a great partnership with the Chicago Transit Authority, where we’re developing a recruitment and retention program and training our population for jobs as diesel mechanics. But it’s been challenging. One, because they need to pass a certification test. We just established a bridge program because diesel mechanic work today is very different compared to 20 years ago. The work is high-tech and computerized and requires good math proficiency.

Kristen: Our governor has put forward a huge local initiative to put more kids in middle-skills careers, so they can start somewhere and earn the money to pay for college or find growth opportunities within that industry. The challenge we’re facing is that some of our youth don’t find these jobs attractive. We’re working on creating private partnerships with businesses to show the students that these careers are something you can look forward to and earn a good living right after high school.

Donnie: We also focus on middle skills, but some of the public-school students we work with are in the remedial classes, so they can't benefit from the technical education courses we offer because of their academic challenges.

AR: How do you get people into programs they aren’t prepared for yet?

Brenda: That’s what I wanted to get at—the importance of bridge programs. It’s about equipping them to pass the entrance exams you need to get into a particular program.

Donnie: Right. How do we bridge those gaps? We're creating internship programs for juniors and seniors that would bridge them to either a two-year or four-year college degree or a certificate. We’re also bringing coding into the schools. A lot of our communities are offering 8- to 16-week coding workshops that are free. We want to bring them into our high schools.

Kristen: That’s really interesting. I just came out of a meeting about the tech industry. Colorado is the third fastest growing state for tech, and we're really trying to grow it. It's a big state initiative. We're a workforce development agency that primarily has focused on soft skills training, right? We don’t want to change our whole curriculum or what we’re good at, but it feels like there’s a bridge missing.

Brenda: Young people get excited about technology. A bridge program to that might be an abbreviated, maybe three- to six-month program to bring them up to a level where they can understand the basic technical academic requirements. Bridge programs take a person from where they are to where they need to be in terms of academic rigor or certifications.

AR: Could you talk about the impact your programs have had, either on the community or directly on the people you’re working with?

Donnie: Our schools have gone from F to A. That’s a result of changing the school culture, getting the students to do enrollment courses, exposing them to opportunities, and increasing the number of students going to college. Five years ago, 50 percent of the students were graduating from high school. Now that number is 85 percent. We’re seeing kids demanding that their teachers teach them more, getting excited about school, and getting angry when their teachers don’t suggest that they go to college

Brenda: That’s amazing. Some of the people we’re working with have been incarcerated for years, and the prison experience is one that strips you of your sense of identity. To go through our programs with caring individuals who help navigate and coach you, and come out with a certification that says you’re ready to work totally restores a person’s sense of self-worth.

Kristen: Our state average graduation rate is 47 percent, but at our schools it’s 83 percent. We’re really making a significant impact, and we’re seeing a lot more businesses come to us and say, “What can you do to help us get in front of youth to look at us as an option for a future career in my organization?” More recently, the city’s Office of Economic Development just chose Goodwill to support their opportunity-youth placement.

Donnie: I’d just like to add the value of mentoring in all these initiatives. I don’t know if the rest of you have had this feeling when you launch new initiatives, but the one piece we really had to look at is: How do we mentor kids for this one? In every program, people need a mentor along the way to keep them motivated to continue.

Kristen: We’ve also found it essential to have mentoring programs within our curriculum, and we use the business community to do that. We bring in middle-skill industries to mentor the youth one-on-one. We also do it during the summer because we feel like so many students drop off in the time between graduation and fall.

AR: Is there anything important you feel you’ve left unsaid?

Donnie: Just that it’s important for the kids we work with to know that whether you’ve been incarcerated, or if you have bad credit, or if you're not sure about what your future is like, there are still people who will wrap their arms around you and say, "Hey, let's try a couple of things," and then stay with your for the long haul until you get on your feet. I’d also like to say thank you for bringing us together for this discussion, because it’s so valuable to hear from colleagues in other cities about how they do their work. I learned a lot.

Kristen: I would echo that. I’d like to have more panels like this.

Brenda: Definitely. It’s so great to know that no matter where you are geographically, we’re all in the work together for a greater cause.

Dialogues like this one show exactly why JPMorgan Chase & Co. works closely with each of these nonprofits and others like them, to help young adults prepare for and find meaningful work that doesn’t require a college degree, and to share what’s working so leaders around the world can address this crucial issue. The company’s commitment to addressing the gap between unemployed youth and skilled jobs – through their New Skills at Work and New Skills for Youth initiatives,– is grounded in the desire to create more economic opportunity for communities and individuals alike.