Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

For many, homeownership is a vital part of the American dream. Buying a home represents one of the largest lifetime expenditures for most homeowners, and the mortgage has generally become the financing instrument of choice. For many families, their mortgage will be their greatest debt and their mortgage payment will be their largest recurring monthly expense.

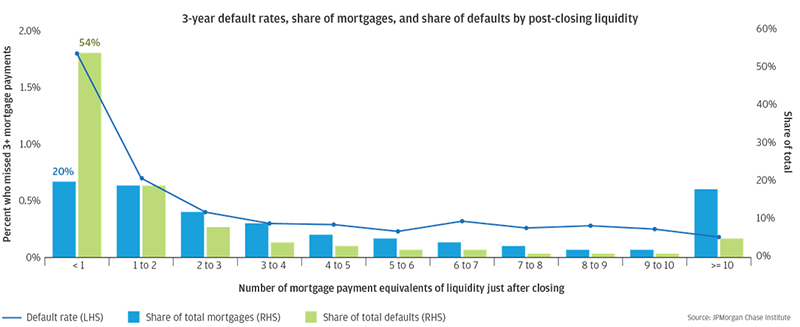

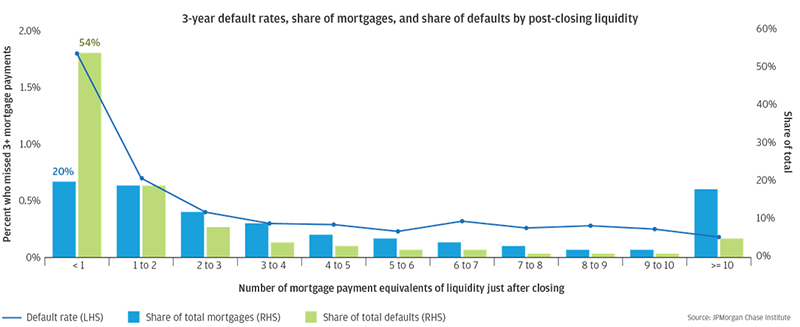

In this report, we present a combination of new analysis and previous findings from the JPMorgan Chase Institute body of housing finance research to answer important questions about the role of liquidity, equity, income levels, and payment burden as determinants of mortgage default. Our analysis suggests that liquidity may have been a more important predictor of mortgage default than equity, income level, or payment burden.

Source: JPMorgan Chase Institute

Taken together, our findings suggest that a program encouraging borrowers to make a slightly smaller down payment and use the residual cash to fund an “emergency mortgage reserve” account might lead to lower default rates. A pilot program could test the impact of an emergency mortgage reserve account on default rates and, if impactful and cost-effective, the program could serve as an alternative to underwriting standards based on measuring the borrower’s static ability-to-repay using their total debt-to-income ratio at origination.

Authors

Diana Farrell

Founding and Former President & CEO

Kanav Bhagat

Director of Financial Markets Research | JPMorgan Chase Institute

Chen Zhao

Housing Finance Research Lead