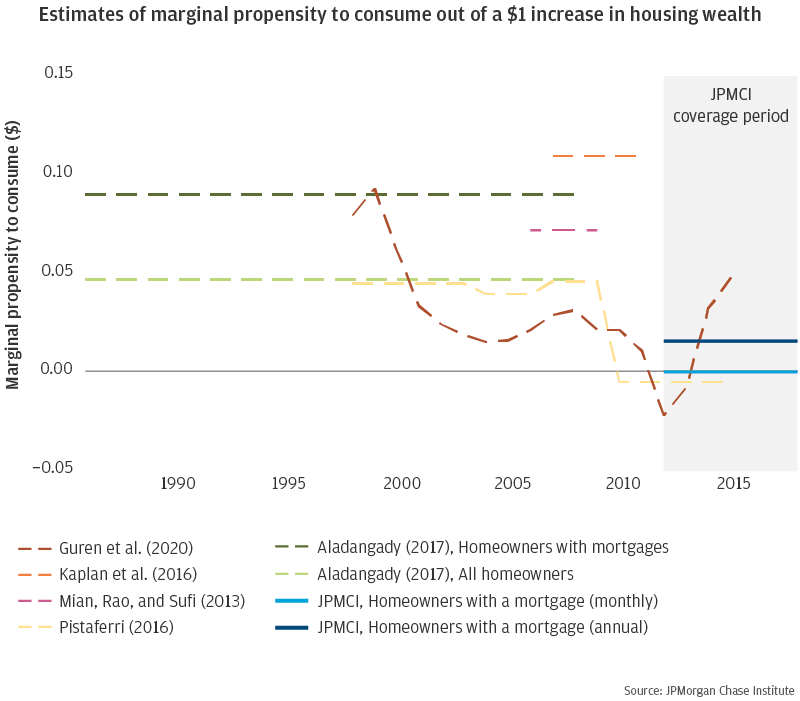

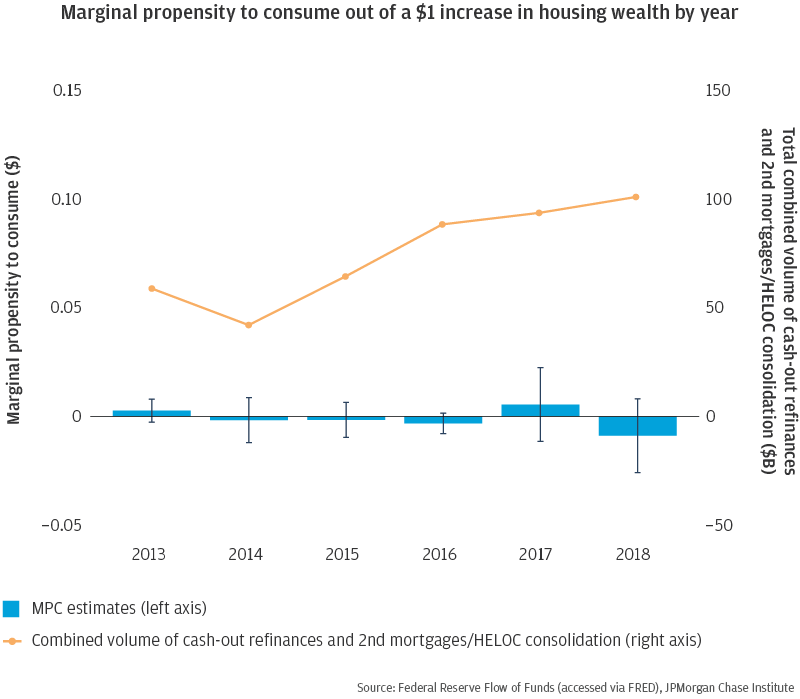

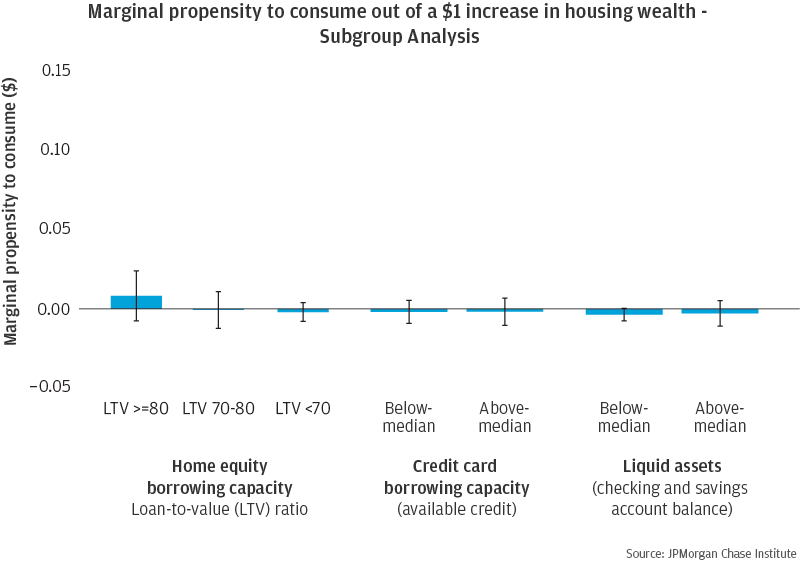

How do we reconcile the much smaller MPC out of housing wealth in the post-Great Recession period with a larger MPC during the preceding periods? We find that the volume of equity withdrawal in the post-Great Recession period was much lower than during the housing boom. Research suggests there are both demand and supply factors at play. After the financial crisis, a larger share of equity became concentrated in the hands of older and less credit-constrained borrowers who tend to have a lower demand for equity extraction. At the same time, tightened lending standards have reduced the supply of credit to more credit-constrained mortgage holders who may have greater demand for equity extraction. We contribute new evidence that a lack of demand to borrow against home equity contributed to a low marginal propensity to consume out of housing wealth: even homeowners with more equity (for whom it should be easy to borrow) did not consume more when housing wealth rose.

This research has several implications for policymakers and is particularly relevant as the economy comes to face a severe recession induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. First, homeowners entered the COVID-19 crisis with a substantial amount of illiquid wealth in the form of home equity. Given the importance of cash flow dynamics and liquidity as determinants of consumption and the ability to stay current on housing payments, measures that allow homeowners to preserve or increase liquidity in the face of financial distress, such as through forbearance or maintaining access to this home equity, could provide an important financial cushion. These types of measures carry risks, however, as home prices could depreciate in a recession, eroding the equity position of homeowners—and increased income volatility could make it more difficult for borrowers to meet debt obligations.

Second, a much smaller housing wealth effect diminishes the ability of conventional monetary policy—changes to short-term interest rates—to affect the real economy through the housing market, resulting in lower consumption and GDP growth than policymakers might have expected or hoped to stimulate. Had the housing wealth effect MPC remained at estimated pre-recession levels, we find that consumption and GDP would have been 0.1 to 1.5 percent and 0.1 to 1 percent higher, respectively, in each of the years from 2012 to 2018. As such, policymakers may need to lean more heavily on other channels of monetary policy and unconventional measures, as well as fiscal policies that provide households with liquidity during an economic downturn.