Conclusion

In this report, we measured the impact of mortgage payment and principal reduction on default and consumption. Our results have implications for both housing policy and monetary policy.

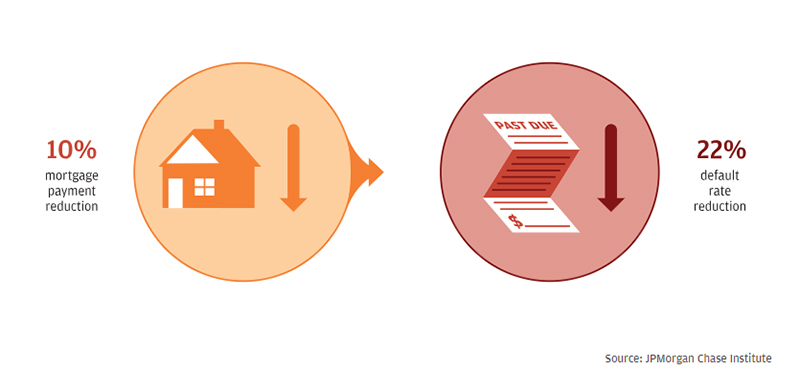

Our findings suggest that mortgage modification programs that are designed to target substantial payment reduction will be most effective at reducing mortgage default rates. Modification programs designed to reach affordability targets based on debt-to-income measures without regard to payment reduction will be less effective. Principal focused mortgage debt reduction programs that target a specific LTV ratio but leave borrowers underwater will also be less effective at reducing defaults.

To the extent that a mortgage modification can be considered a re-origination, our findings may have application to underwriting standards as well. The fact that default was correlated with income loss provides evidence that static affordability measures such as debt-to-income ratio were not a good predictor of default. Both high and low mortgage PTI borrowers experienced a similar income drop just prior to default, suggesting that even among those borrowers whose mortgages would be categorized as unaffordable by conventional standards, it was a drop in income rather than a high level of payment burden that triggered default. Therefore, policies that help borrowers establish and maintain a suitable cash buffer that can be drawn down in the event of an income shock or an expense spike could be an effective tool to prevent mortgage default.

The housing wealth effect is one of the important mechanisms that transmits changes in monetary policy to household consumption. This transmission mechanism relies on accommodative monetary policy leading to higher house prices, and the increase in housing wealth that in turn stimulates consumption. The lack of consumption response from underwater borrowers to principal reductions suggests that the marginal propensity to consume out of housing wealth is nearly zero for these homeowners. For underwater borrowers, the inability to translate increased home equity into liquid resources (e.g., through equity extraction) may nullify the housing wealth effect and thus constrain this transmission mechanism.