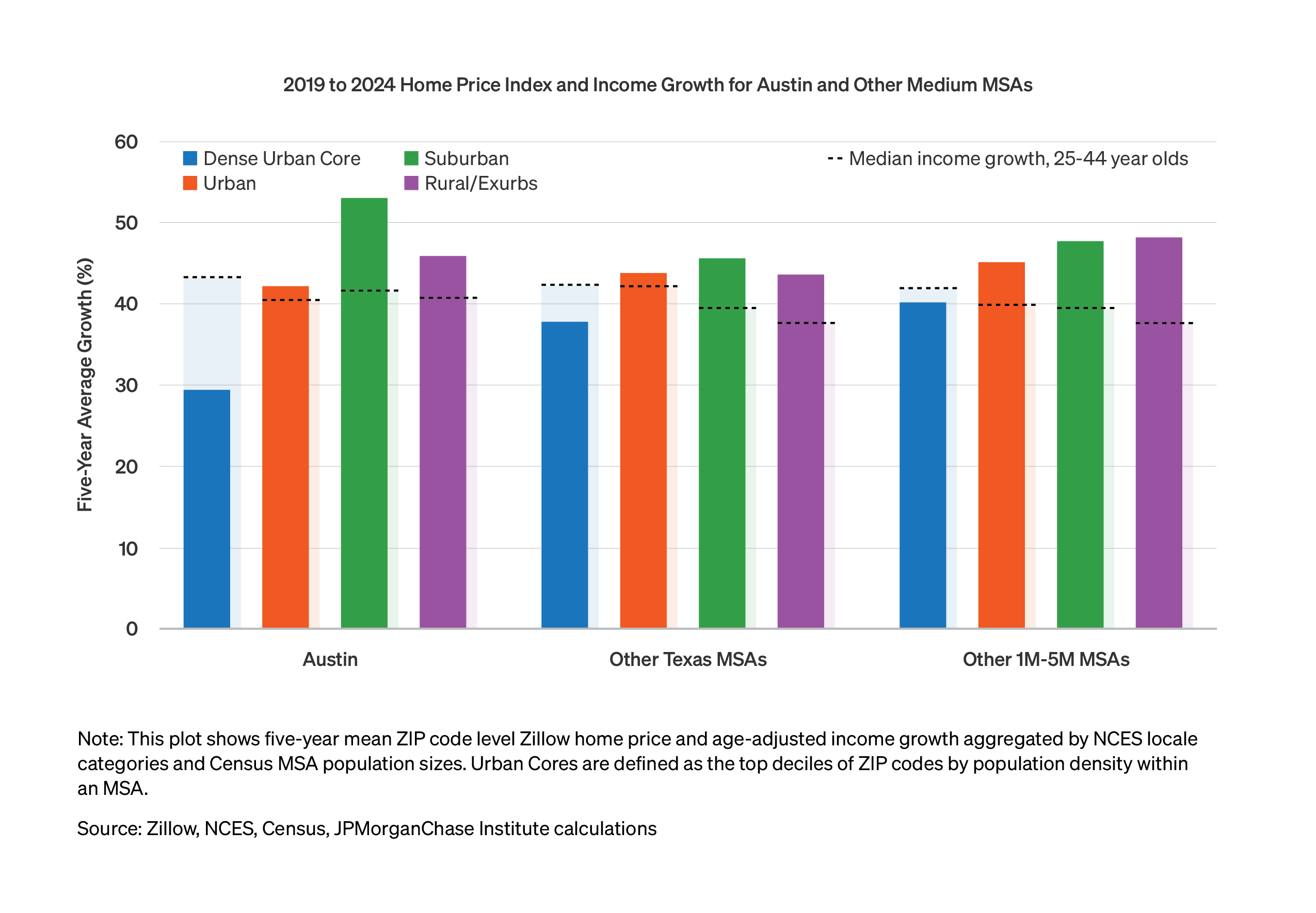

A bar chart showing both five-year average Zillow home price growth and age-adjusted median income growth for 25 to 44 year-olds from 2019 through 2024, by urbanicity classification, for the MSA of Austin, the average of Other Texas MSA’s, and the average Other US MSA’s with Populations Between One to Five Million.

For Austin, Other Texas MSA’s and Other MSA’s with Populations One to Five Million, the figure shows a bar for four urbanicity classifications from left to right: Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, both the Zillow five-year price growth (Solid Bar) and the five-year average growth in age-adjusted median incomes for 25 to 44 year-olds (Faint Bar), with the Faint Bar behind the Solid Bar, slightly wider, and with a black dotted line at the top of the bar.

The Solid Bars for Austin, read approximately: 29 percent, 42 percent, 53 percent, and 46 percent for Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, respectively. The Faint Bars for Austin, read approximately: 43 percent, 40 percent, 42 percent, and 41 percent for Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, respectively.

The Solid Bars for the Other Texas MSA’s, read approximately: 38 percent, 44 percent, 46 percent, and 44 percent for Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, respectively. The Faint Bars for Other Texas MSA’s, read approximately: 42 percent, 42 percent, 40 percent, and 38 percent for Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, respectively.

The Solid Bars for the Other MSA’s with Populations One to Five Million, read approximately: 40 percent, 45 percent, 48 percent, and 48 percent for Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, respectively. The Faint Bars for Other MSA’s with Populations One to Five Million, read approximately: 42 percent, 40 percent, 39 percent, and 38 percent for Dense Urban Core, Urban, Suburban and Rural/Exurbs, respectively.