A week after the release of a tough report that shows long-standing racial gaps costs the Columbus economy $10 billion a year, the CEO behind the report called for a raise in the minimum wage, making mortgages more affordable and helping lower-income workers learn new skills that can put them into higher-wage jobs.

"All of these things we have to work on," Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase & Co., told The Dispatch in an interview Tuesday.

Chase, the largest private employer in Greater Columbus, financed the report, called Advancing Workforce Equity in Columbus: A Blueprint for Action. The report said historical inequities are hurting the Columbus economy and the region's workforce remains largely segregated.

"I would raise the minimum wage," he said. "We can get more income into the hands of lower income workers."

He said he supports expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit that helps low- to moderate-income families and that apprenticeships are vital to helping people learn skills that can give them jobs with starting wages of $45,000 to $65,000 or more.

Over the years, JPMorgan has established a variety of job-training initiatives with Columbus City Schools, Columbus State Community College, Otterbein University, Ohio State University and other educational programs with the goal of helping prepare workers in underserved communities for jobs that employers struggle to fill.

Business also need to work with local schools when it comes to training, he said.

"It can't be one against the other," he said.

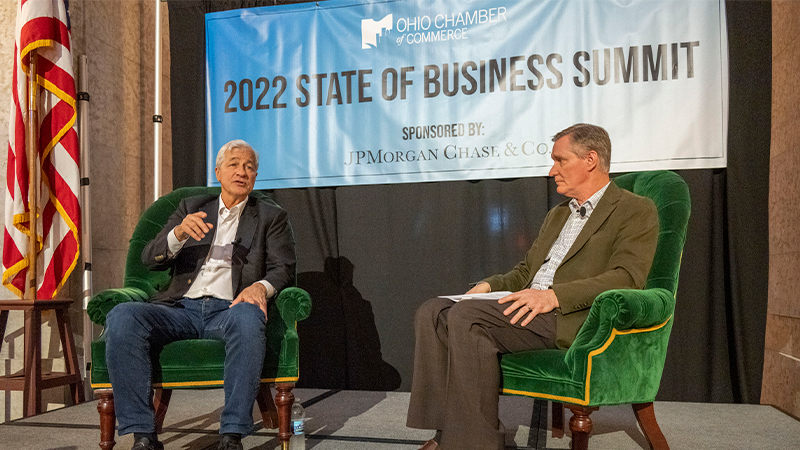

Dimon, who also spoke at an Ohio Chamber event Tuesday night at the Statehouse with chamber CEO Steve Stivers, has talked of the need of giving people with a criminal history a second chance when it comes to employment and pushing employers to reconsider whether a job really requires a four-year degree.

"Give people a chance, and you'll get dedicated people who want to have those jobs," he said at the event.

Dimon complained about regulations that make it tougher than necessary to hire workers.

"It's staggering what you have to go through to get someone hired," he said.

Dimon said most families build their wealth through their home, and home ownership rates for white families are far higher than rates for minority families.

"A lot of minorities have what are called thin credit files. Rent doesn't count in a credit file. If you've been paying rent for 20 years you're probably a pretty good credit so we want to extend credit," he said.

But Dimon says while the federal and state government can be a part of these efforts, the effort should be on coming up with local initiatives to address inequities. JPMorgan Chase helped fund one such effort this week in Columbus, a program designed to boost affordable housing while building the ranks of minority developers.

"You don't want the federal government or JPMorgan to dictate solutions," he said.

Are we in a recession?

"We are not in a recession," Dimon said. "We have a very strong economy and that's going to continue."

Consumers have money to spend and household and business balance sheets are in good shape, he said.

"But there's storm clouds ahead, not tornadoes. So we don't know how it's going to turn out, but the storm cloud are inflation, which is not transitory. It's going to be around for a little bit," he said.

Rising costs for commodities, wage pressures and the Ukraine-Russia war are putting pressure on the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates.

Dimon said the Federal Reserve is attempting to engineer what's called a soft landing where it is successful in bringing down inflation without putting the economy into recession.

The best case is that inflation, which is running at a 40-year high, comes down to 4% by year's end, he said. The worst case is that inflation continues to climb to perhaps 10% and the Federal Reserve has to be even more aggressive, he said.

"We simply don't know. We're hoping for the best," he said.

The trillions of dollars pumped into the economy during the pandemic by the federal government and the Federal Reserve gets most of the blame for inflation, he said.

Supply chain problems, the war in Ukraine and other factors have contributed, he said.

"That clearly aggravated it, but it would have happened anyway," he said.

Columbus key to JPMorgan

Columbus has about 18,000 Chase workers involved in a variety of banking operations from credit cards to technology to watching cyber threats.

"It's a fabulous operation," he said.

"There's a vibrant workforce, smart, efficient people, and they want to be here," Dimon said.

He credited Columbus with having a growing population, affordable housing and good choices when it comes to higher education. It also a city that welcomes business, he said.

"Those towns that are antibusiness make a huge mistake. ... Business goes where it's treated well."

Intel's effect on the Columbus economy

Dimon said Intel's decision to invest $20 billion into building two factories in Licking County is the start of building an ecosystem that is going to be a magnet for other companies.

"Once it starts, you're absolutely going to have other things," he said of the ecosystem that will be created around Intel in coming years.

Dimon said it is important to return semiconductor production to the U.S. or friendly countries because of the critical importance chips play in the economy.

"I want the guy to succeed," Dimon said of Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger. "He's the real thing. It's great for Ohio."

Regulations hurt the economy

Dimon told the audience of about 175 legislators and business leaders at the Statehouse that he wished the country was more focused on economic growth and that regulations hurt the economy in areas such as affordable housing, developing wind and solar farms, taxes and having a good workforce.

"We grew at 2% the last 20 years. It should have been three-and-a-half percent. That one-and-a-half percent is like $10,000 per person at the end of the 20 years. That would pay for a lot of stuff in this country," he said.

This story originally appeared in the Columbus Dispatch