The experience of unemployment is nearly universal. Surveys show that over 90 percent of baby boomers have had at least one unemployment spell, and, every year, about one in four working adults experience a period of joblessness. These individuals face a substantial income loss. In Paychecks, Paydays, and the Online Platform Economy, we documented the high degree of income volatility that families experience. Unemployment insurance (UI) benefits provide wage replacement for individuals in the event that they lose their job. In this report, we evaluate the role that UI plays in mitigating the financial impacts of job loss, which is a key source of income and expense volatility. Our report is a first-ever look into comprehensive and high frequency measures of spending behavior among a large sample of the unemployed in the US.

Although the UI system is intended to protect workers against the consequences of job loss, most unemployed workers do not receive UI. Roughly 90 percent of workers have the types of jobs that make them eligible for UI, but many unemployed people are still ineligible for a variety of reasons. Other unemployed people have already exhausted their unemployment benefits. In total, just 27 percent of unemployed people nationwide, roughly two million individuals a month, received unemployment insurance in 2015. This is the lowest recorded recipiency rate since World War II. In some states with particularly restrictive eligibility requirements, such as Florida, Georgia, and Louisiana, fewer than 15 percent of jobless workers received UI in 2015, compared to more than 70 percent in North Dakota. The level and duration of unemployment insurance benefits also varies by state. These benefits are typically intended to replace 30-50 percent of pre-tax wages on a weekly basis for up to six months or until the individual finds another job.

With the rapid growth of independent contractors, record low labor force participation rates, and an increase in the share of total unemployed who are long-term unemployed, the fraction of Americans working in traditional W-2 employee arrangements with eligibility for benefits, such as UI, is shrinking. These trends have stirred lively debates about the future of work and how the social safety net might be redesigned for the 21st century.

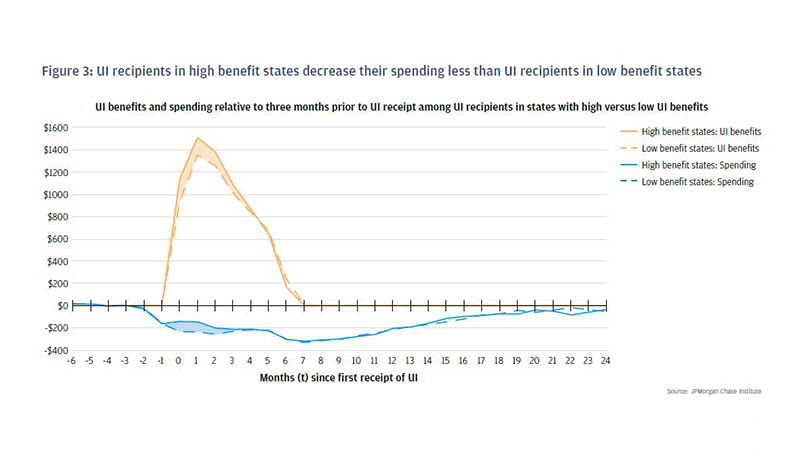

This report informs three key debates regarding UI reform and the social safety net more broadly. First, there have been recent policy proposals to expand coverage of UI benefits to part-time workers and those who must leave a job due to compelling family reasons or family illness. We contribute to this debate by estimating how much of the potential spending drop from unemployment is averted by UI based on a comparison of UI recipients in states with high versus low UI benefits. Second, in the wake of the Great Recession some states have cut maximum benefit durations below the traditional 26-week norm. In response, advocates have proposed a federal requirement that states offer up to 26 weeks of benefits. We can assess the impact of this proposal by comparing the spending trajectory in Florida—which offered 14 weeks of benefits in 2015—to spending trajectories in states that offer 26 weeks of benefits. Finally, some proposals seek to make the social safety net more portable, by, for example, establishing “individual security accounts” based on pro-rated employer contributions. We explore how liquid assets levels—a proxy for the potential safeguard of individual security accounts—are correlated with spending levels after job loss.

Our dataset offers good coverage of the financial lives of UI recipients. From a universe of 28 million Chase checking account customers we rely on an anonymized sample of 160,000 regular Chase customers who received unemployment insurance between 2014 and 2016 across 18 states. To be eligible for UI benefits, a claimant needs substantial work history in the prior year. As a result, the typical UI recipient is a middle-income household with a bank account. Subjects in our dataset who receive direct deposit of their UI benefits have similar incomes, spending levels, ages, and checking account balances to external benchmarks from public use datasets, suggesting that our results here are likely to generalize to all UI recipients.

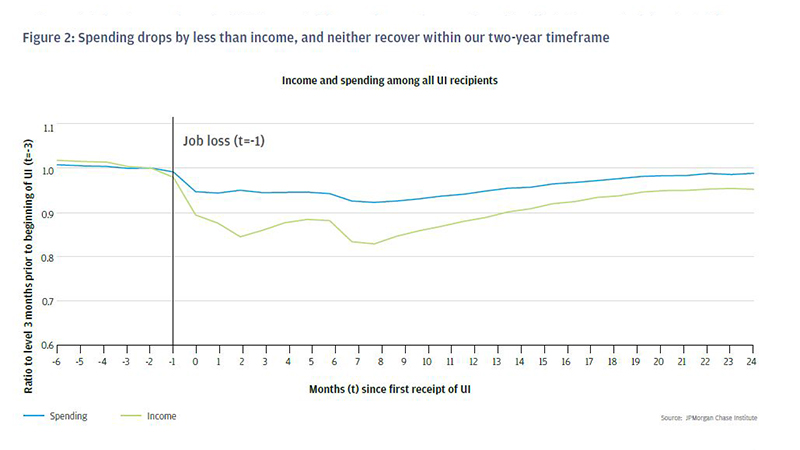

Our results show that UI is remarkably effective at preventing large spending drops among the short-term unemployed. We organize our results into five findings. First, UI softens the drop in family income due to job loss from roughly $1,826 a month—a 46 percent drop in monthly income—to just $617 a month—a 16 percent drop. Second, spending drops by just 5 percent upon job loss because UI benefits boost spending dramatically, averting 74 percent of the potential drop absent UI. Third, spending declines coincide with income losses. Income and spending recover within 18 months for the short-term unemployed but remain depressed for the long-term unemployed. When UI benefits are less generous, the long-term unemployed experience more economic hardship but also go back to work sooner. Fourth, among all UI recipients, job loss causes a drop in discretionary spending and student loan payments, but the long-term unemployed cut nearly every category of spending when UI runs out. And finally, families with high liquid assets reduce their spending upon job loss by roughly half as much as families with low liquid assets.