Conclusion

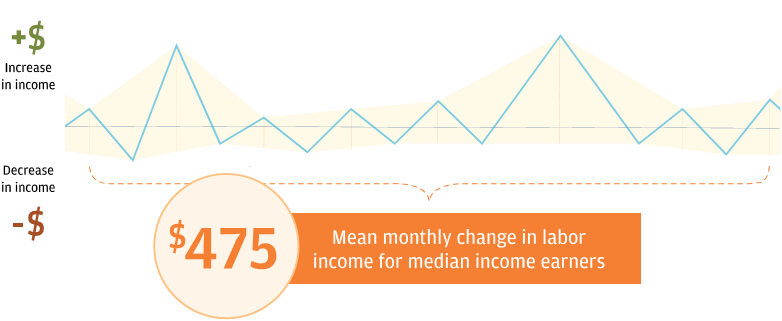

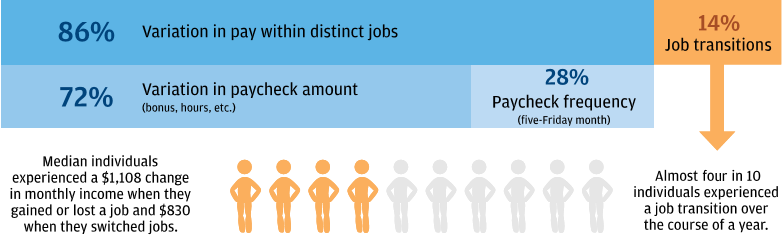

The findings in this report underscore the importance of asset building so that families have enough liquidity to weather volatility in income and spending. Key, predictable savings opportunities include December to March pay spikes, five-Friday months for individuals with jobs that pay every two weeks or weekly, and tax season for those who receive tax refunds. The five-Friday effect also reveals a structural disconnect between typical employer pay cycles and billing cycles. Eighty percent of individuals received an extra paycheck in five-Friday months because they held a job that paid every two weeks or weekly. Meanwhile, 40 percent of expenditures, including rent payments and installment loans, have a fixed per-month expense regardless of the number of days in that month. These fixed costs are potentially easier to cover during, or shortly after, months with an extra paycheck. Employers, financial institutions, utilities, and landlords can ameliorate this mismatch by offering paycheck cycles that sync with payment cycles or vice versa.

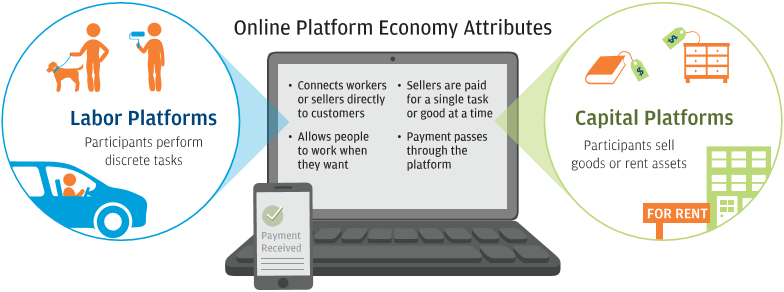

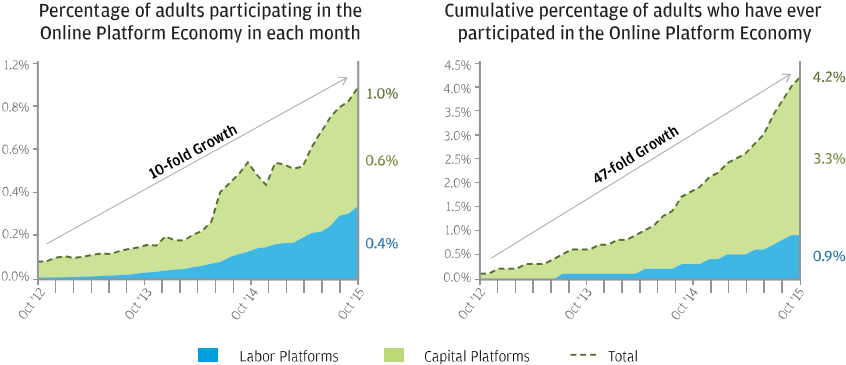

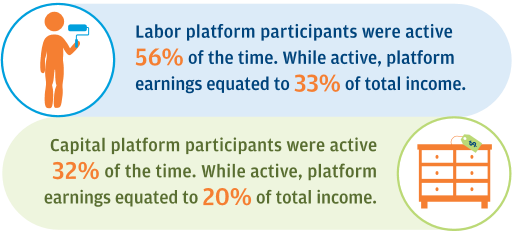

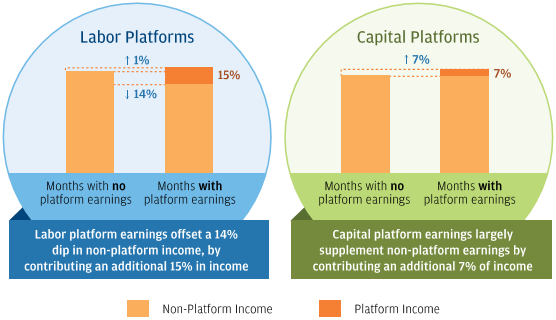

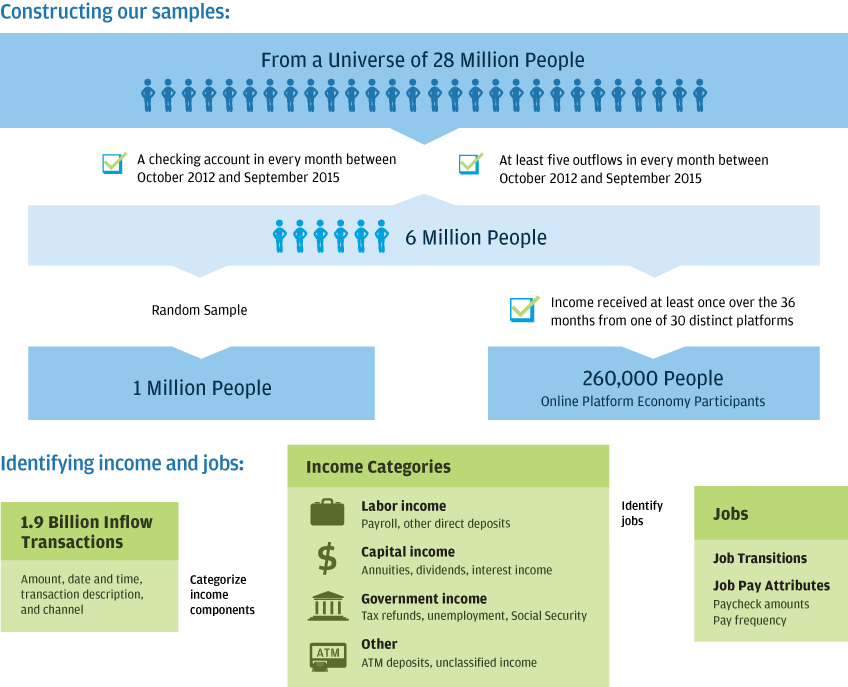

This study is the first of its kind to shed light on the Online Platform Economy using financial transactions, and provides an important foundation for the many policy and economic debates related to what some have termed the “future of work.” Over the three years of our study (October 2012 to September 2015), 4.2 percent of adults, an estimated 10.3 million people—more than the total population of New York City—earned income on the platform economy. This number increased 47-fold over the three years. We distinguish between labor platforms and capital platforms and find that, although labor platforms grew more rapidly than capital platforms, participation on capital platforms was more than 60 percent higher than participation on labor platforms. Although the sheer number of people participating grew rapidly, platform earnings remained a secondary source of income, and reliance on platform earnings did not increase for individuals over time.

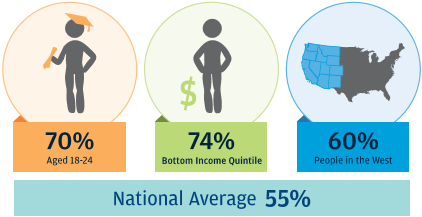

The Online Platform Economy adds an important new element to existing labor markets, however. Simply put, landing a platform job is easier and quicker. Individuals can, and do, generate additional income on labor platforms in a timely fashion when they experience a dip in regular earnings. This is a potentially far better option to mitigate or weather volatility, if the alternatives are to constrain spending or take on additional credit. Moreover, this option meets a target need. Participation in labor platforms is highest precisely among those who experience the highest levels of income volatility—the young, the poor, and individuals living in the West.