Conclusion

In this report, we brought new data to two conversations about the economic contributions of the small business sector—a first concerning the large contributions of a potentially small set of high-growth businesses, and a second concerning the contributions of the majority of small businesses to widespread and diverse economic growth. We use these data to offer two new frameworks in which to consider these questions—a revised segmentation of the small business sector, and a new typology of cash flow patterns.

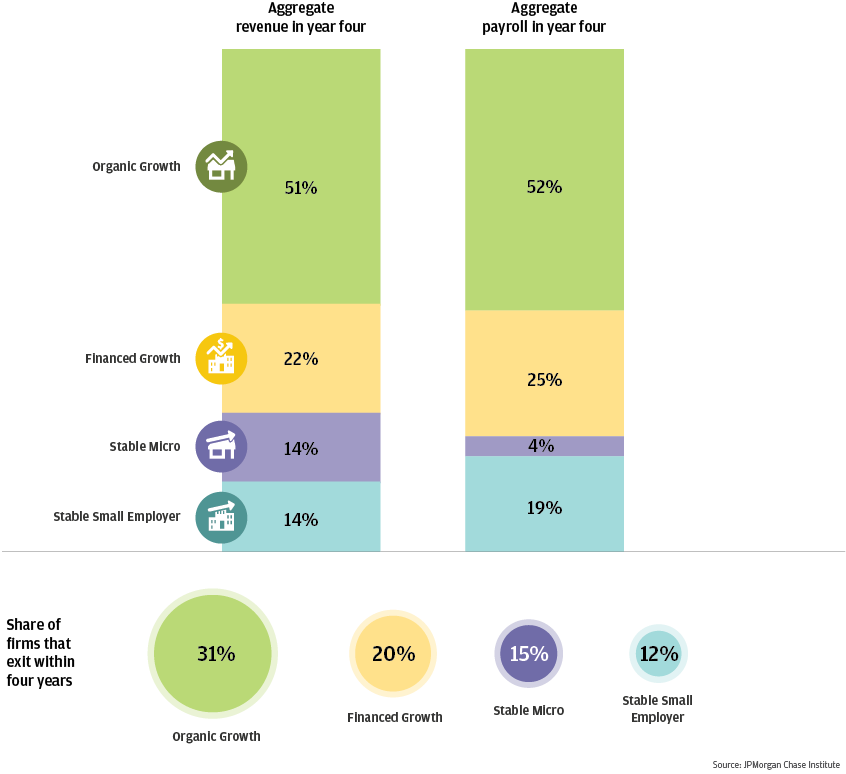

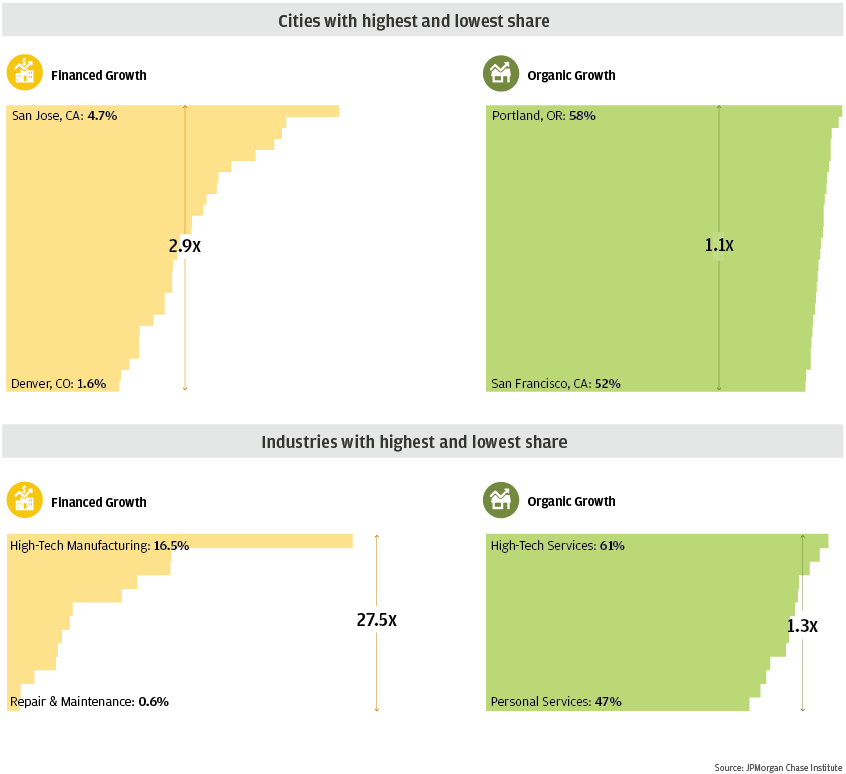

Our findings highlight the existence and economic importance of a large segment of dynamic small businesses that grow organically without heavy reliance on external financing. In aggregate, these small businesses generate substantial shares of both revenue and payroll, and importantly, are widely distributed across regions and industries. While the nonemployer small businesses that make up the majority of the sector are unlikely to transition to employer status, many are nevertheless important when viewed through other lenses of economic growth.

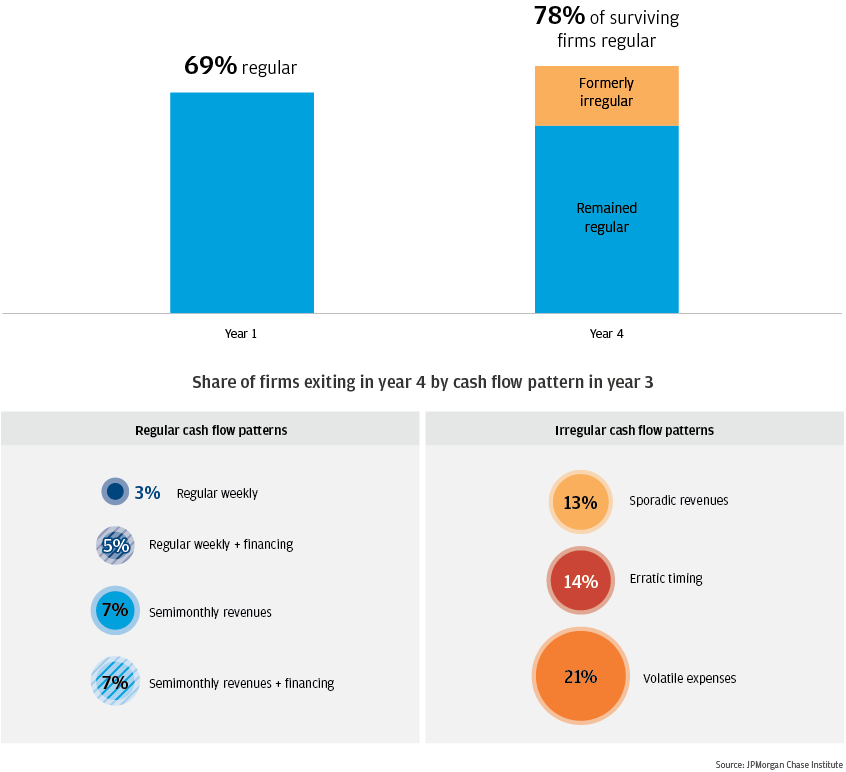

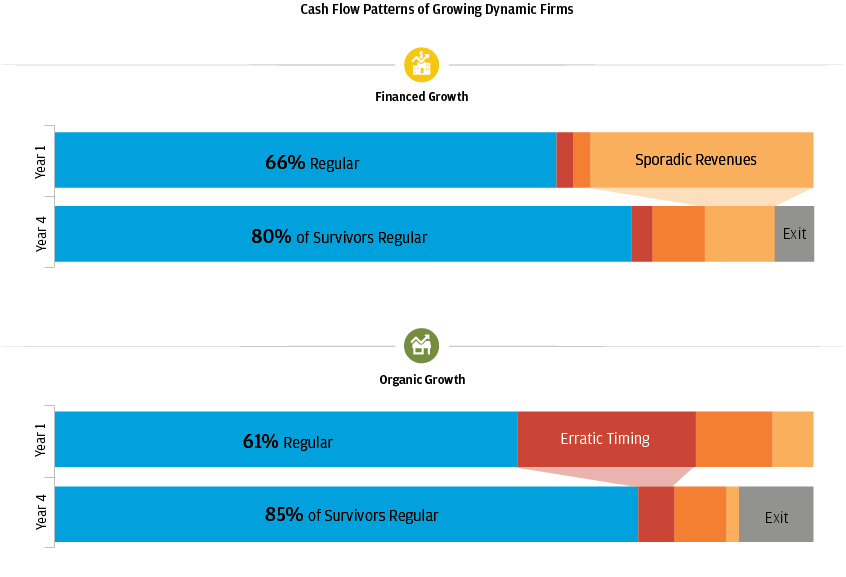

Our findings also offer a first high-frequency view of the cash flow dynamics of small businesses. Across the board, small businesses have volatile, irregular, and potentially unpredictable cash flows. Many small businesses transition to more regular cash flows as they age, though many that fail to do so exit. Notably, the kinds of cash flow issues that small business navigate vary meaningfully by segment—financed growth firms were particularly likely to face and resolve cash flow problems related to the uncertainties around revenue, while organic growth firms were more likely to experience a broader array of unexpected cash flow timing.

These findings suggest that policy makers interested in economic growth have an opportunity to focus on a wider range of small businesses than the financing-intensive high growth firms that often are the focus of small business policy, and that opportunities for productive action may exist across a wider variety of regions and industries than previously thought. While the irregularity of cash flow we observe across segments warrants a continued focus on ensuring that small businesses have sufficient liquidity to grow, our findings suggest that programs that help small businesses better manage their cash flows may be equally, if not more, impactful in supporting the overall growth of the U.S. economy.