Please update your browser.

Stories

A Black Family's History of Escape and Triumph

Myles Luster's family always knew about their rich history after slavery ended. But a curious uncle's research led to new surprises—and a meeting with the family that once owned their ancestors.

Growing up, Myles Luster—a private client advisor with J.P. Morgan and member of JPMorgan Chase's Black Leadership Forum—was surrounded by his family history.

At reunions on the family farm in Oklahoma, he'd listen to stories about his great-grandfather who escaped from slavery, his great uncle who fought in World War I, and his grandfather, the first black postman in Oklahoma. He'd hear the memories, see the pictures and walk the land that had been in his family for three generations.

But when his Uncle Walter started doing family research, he discovered there was a lot he didn't know.

Myles' uncle, Walter Luster, Jr., retired from his job as a prison warden in the early 1980s, and devoted himself full-time to researching his genealogy. At family reunions, he'd share the latest information with Myles. “Every time I came home from college, Uncle Walt would pull out all this data—documents, deeds, pictures—and we'd have hours of conversation about it," Myles recalls. “I would write pages and pages of notes, just so I could remember what he was showing me."

Walter's story began in the 1870s with a boy who escaped from slavery. And that story, Myles learned, continued through to his own life—and beyond.

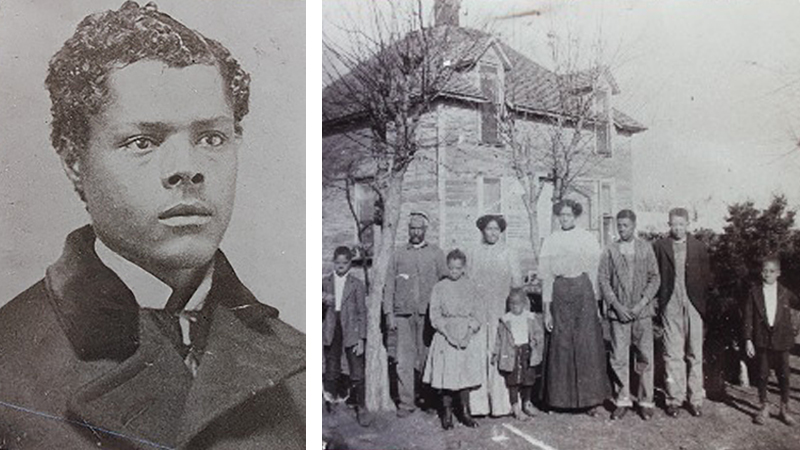

Left: Newton David Stubblefield (1862-1939). Right: Newton David Stubblefield, Mary Ann Stubblefield and family in front of their home in Logan County, Oklahoma.

Left: Newton David Stubblefield (1862-1939). Right: Newton David Stubblefield, Mary Ann Stubblefield and family in front of their home in Logan County, Oklahoma.

A History Born in Slavery

Newton David Stubblefield—Myles' great grandfather—was born on a Texas plantation in 1862, while the Civil War was still raging. The lady of the plantation had a son at the same time, and both children had the same father—the doctor who owned the farm.

Newton and his half-brother played together, and the slaveowner's son taught Newton to read and write, which was rare at the time. “He didn't know what he was giving Newton," Myles says. “It was the ability to function in society as a former slave."

On June 19, 1865—a date that is celebrated today as “Juneteenth"—Texas accepted the Emancipation Proclamation, making it the last of the Confederate states to free its slaves. But on the farm where Newton lived, his situation remained unchanged until six years later, when he ran away to Oklahoma at the age of nine.

The Oklahoma territory had been settled by Native Americans in 1830, after the infamous “Trail of Tears," when the federal government forced them out of the Southeastern United States. In the following years, it became a haven for Black people searching for freedom and opportunity. “Together, the native Americans and African Americans found security and built communities," Myles says. “Between 1865 and 1920, over 50 incorporated all-Black townships developed in Oklahoma. Greenwood, site of the Greenwood massacre, was one of them."

In Oklahoma, Newton met Jim and Molly Hall and their nine daughters. The family took him in and put him to work. He became a horse trader, a job that made use of his education and eventually gave him the means to marry the Hall's oldest daughter, Maryann. Together, they moved to another town. “We have a document showing how, in 1910, he bought 160 acres of land for $3,000 cash," Myles recalls. “If he hadn't known how to read and write, he couldn't have made that money, negotiated that price, and bought that farm. The land is still in our family today."

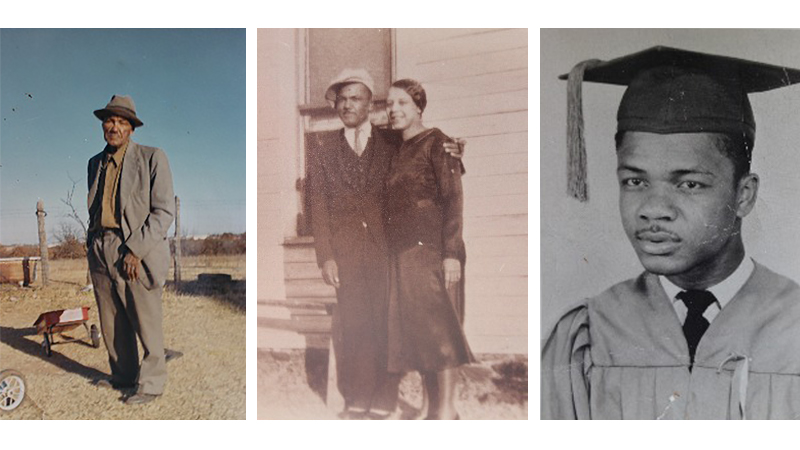

Newton and Maryann Stubblefield raised livestock and grew vegetables, which they sold in the nearby town. They donated their surplus to help support the neighboring Black community. When Newton's daughter Inez (Myles's grandmother) moved to Oklahoma City with her husband, Walter Luster, Sr., she repeated the process—building a farm and giving her surplus to the surrounding community. Walter became Oklahoma's first black postman, and together the couple made enough money to buy two motels, creating a legacy for their family.

A Painful History—And an Incredible Story

Walter Luster Jr.'s genealogical research ultimately took him to Denton, the Texas town where his family story had—in many ways—begun. After visiting the grave of his great grandfather, the slaveowner who had owned Newton, he decided to see if he could track down any surviving members of the family. He eventually found four of them, and they met at the local library.

It was a cordial meeting, Walter later recalled. The slaveholder's descendants knew the family history—they even knew about Newton—but they had no clue about what happened after he escaped. Walter filled in some of the details.

When he returned to tell his family about the meeting, their response was a mix of curiosity and shock. “We already knew our family history, so it wasn't like we were reading a book, where you're kind of removed from it," Myles says. “There was some anger, but not so much at the slave-owning family. More at the fact that our family had suffered through this experience."

A few years later, Walter went back to Texas where he met with another member of the family, a fellow great-grandson of the slave owner, with a deep interest in genealogy. He was amazed at Walter's stories of his family. “It's an incredible story—how an African-American family could come from slavery, with nothing, and build this rich history and tradition. To go from being property to being successful," Myles says. “We still have a picture of that meeting. On the back, my uncle wrote 'Great Grandsons.'"

Left: Walter Luster Sr., Center: Walter Luster Sr. and Inez (Stubblefield) Luster, 1928, Right: Walter Luster Jr.

Left: Walter Luster Sr., Center: Walter Luster Sr. and Inez (Stubblefield) Luster, 1928, Right: Walter Luster Jr.

A Rich Inheritance

Newton always emphasized how important his early education had been to his success. “He insisted that everyone in his family learned to read and write," Myles says. “And that's been the same thing with my family. My cousins, aunts, uncles, siblings—we pretty much all have college degrees."

While most of Newton's children were educated at home, many members of the next generation went to historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) like Dillard, a college in New Orleans where Myles' Uncle Walter got his degree. In the following generations, as opportunities became more available, Myles and his cousins went to schools around the country.

Myles' mother's family also emphasized education. His maternal great-grandmother, Doshie Branch, was born in 1910, the child of Black and Native American parents. “She always asked me the same question: 'Are you still in school?,'" Myles recalls. “I was six or seven years old, but I'd always tell her 'Yes, grandma, I'm still in school.' Then she'd say 'Good. The one thing the white man can't take from you is your education.'"

Today, Myles continues Newton's tradition. “One of my daughters is in college and the youngest—she's 13—is already looking at colleges," he says. “I tell them, 'Understand that you have to be twice as good, learn twice as much and have twice the experience to be successful in this country. Period.'"

Living the Legacy

Myles' emphasis on education carries into his work at J.P. Morgan. “At the end of the day, my role as Vice President-Investments and Private Client Advisor is to help people make smart decisions," he says. “A lot of that is helping them understand their own situation, in terms of how to create a smart retirement plan and a legacy for their family."

As part of JPMorgan Chase's Black Leadership Forum, Myles also continues his family tradition of serving the community. “There are three prongs to the BLF," he says. “Advocate for Black opportunity within the bank, recruit other potential Black employees, and engage with the community itself." As part of its outreach, the BLF works with community organizations, Black-owned businesses and HBCUs, like the ones that educated many members of Myles' family.

Myles says that his family history—both the struggle and triumph—continues to inspire him.

“Living under slavery, Jim Crow, racial injustice, inequality and lack of opportunity to get to where we are today—it's a miracle," he says. “Not just for my family, but for the millions of other African-American families that have gone through the same thing."