Please update your browser.

Stories

A Working Education

How students are learning the skills they’ll need to fill the biggest hole in the American job market.

Five young cooks move methodically around a professional-grade kitchen, pouring flour and eggs into a stand mixer, scooping balls of snickerdoodle dough onto baking sheets, peeking into ovens to ensure nothing burns. They’re filling their largest order to date: 300 holiday cookie tins, to be sold at a local hotel. Chocolate chip and peanut butter cookies are cooling on a table in the center of the room, waiting to be packaged and sent out.

It’s the type of culinary production that usually demands the experience and skill of professional bakers. But these bakers, though certainly skilled at their craft, are still high school students. The kitchen is their classroom at Lenoir City High in Lenoir City, Tennessee, and the class is part of the school’s Career and Technical Education (CTE) program.

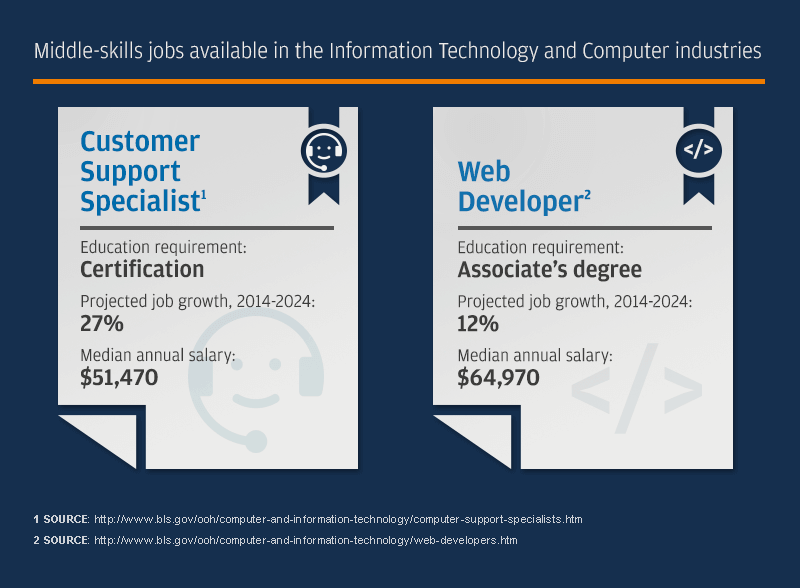

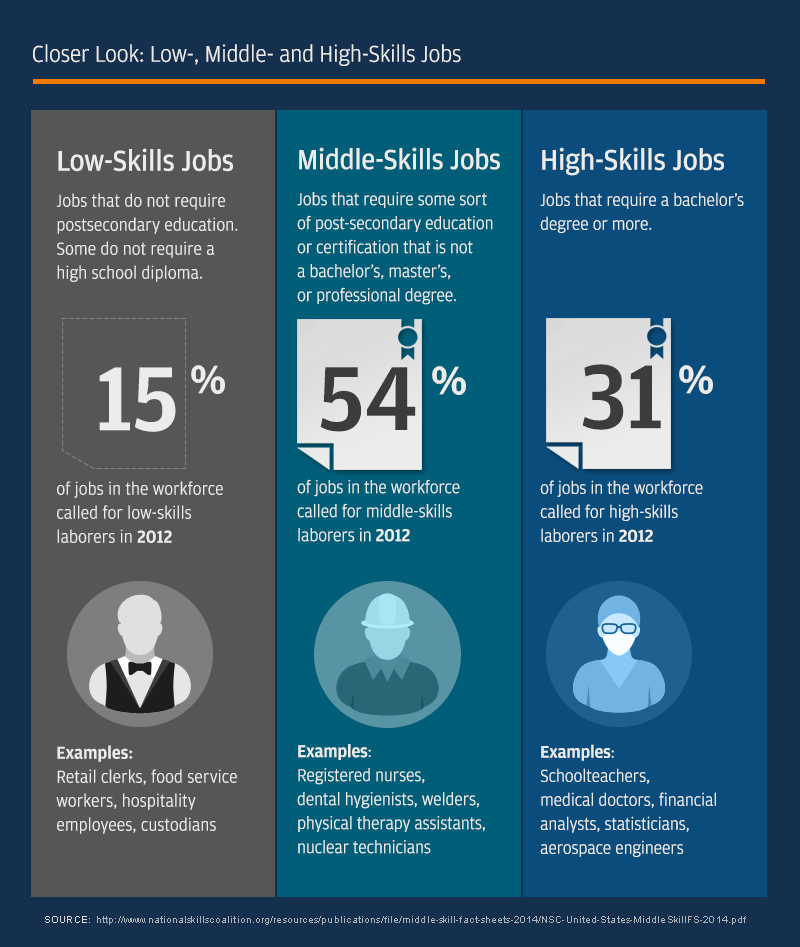

At times called vocational education, CTE class curriculums generally focus on middle-skills jobs --those that require more than a high-school diploma but less than a four-year degree. While career-focused students have long been encouraged to focus on academics and pursue a four-year college degree, CTE classes were once seen as a place reserved for students who couldn’t quite cut it academically.

Now, sparked by a combination of mounting student debt and a high unemployment rate amongst the millennial generation, CTE is gaining renewed, bipartisan focus across the country. Attention has shifted from the four-year-degree conversation to a spotlight on preparing students for life after high school, says Kate Blosveren Kreamer, deputy executive director of a national nonprofit that represents state leaders and directors responsible for CTE programs. She notes that this change in the conversation offers students “career awareness [and] some career exposure.”

A Renewed Focus on Middle Skills

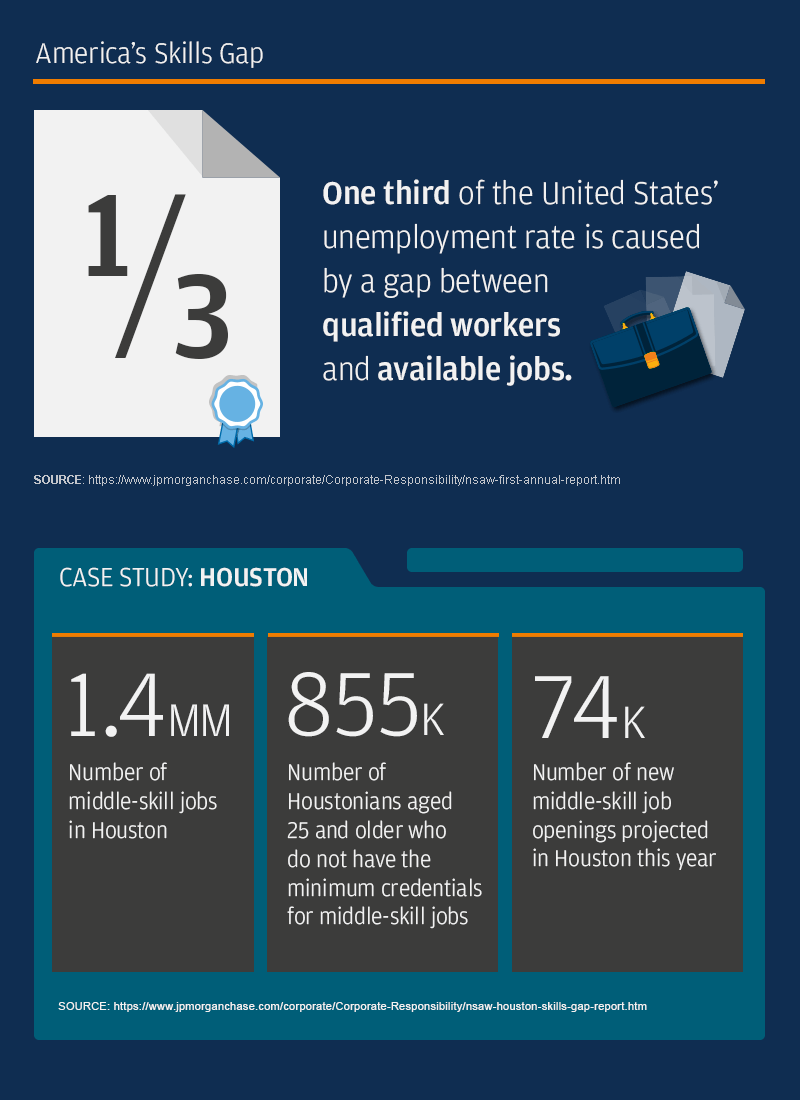

For many young people, the four-year-degree path hasn’t panned out as promised: 45 percent of recent college graduates are underemployedf1. Young people make up 40 percent of the unemployed population in the U.S., and hold an average of $30,100 in student debt2.

In 2012, middle-skills jobs accounted for 54 percent of the nation’s jobs, eclipsing the amount of both high-skills jobs and low-skills jobs combinedf3. Despite the millions of young people looking for jobs, nearly six million middle-skills jobs are currently unfilled4.

Recognizing a missed opportunity, educators and policymakers on both sides of the partisan aisle are motivated to teach students the skills they’ll need to qualify for these roles. It’s an effort that will impact future workers on a personal level as well as the prosperity of local communities and the growth of the national economy.

Last year, the federal government awarded more than $1 billion in grants for CTE programs. Private companies are donating equipment and funds, too, in an attempt to help bridge the gap. The efforts appear to be paying off, with an estimates showing that up to 96 percent of U.S. high school students now take at least one CTE course, including 237,425 students in Tennessee alone5.

Courses Designed for the Modern Job Market

Whenever possible, CTE classes take place in rooms that resemble their professional equivalents – from scale-model of a courtroom to a dentist’s office, a fully-functioning coffee shop, a working farm, or hair salon – and they’re taught by former industry professionals. At Lenoir City High, a former respiratory therapist teaches an emergency-responder course and a veteran engineer teaches freshman how to pressure test a scale-model of a bridge.

Hearing their teachers describe what it’s really like to work in a given field can be as beneficial to students as the coursework itself. It was during his senior engineering class that one Lenoir City senior, Dawson Hope, realized he’d rather study something else in college. Hope now plans to study computer science or information technology at Pellissippi State Community College next fall, a school where at least 70 percent of students change their major at least once. He’s hoping he’ll avoid that fate, thereby saving time and money. He’s also now working in his school’s computer repair center, which is run by teachers and other students like himself, to make sure he’s right about his decision.

Whether he eventually leans towards engineering or computer science, Hope is well equipped to eventually earn a job in his region, as CTE program directors work closely with local chambers of commerce to tailor courses to the needs of local industries. At Stewarts Creek High School, that means audio production students aren’t simply chasing a pipe dream: They’re developing the skills that give them an edge in nearby Nashville. Senior Jaylen James is already working in the industry, selling beats to professional musicians who find his work online.

This focus on regional opportunities affords administrators a level of flexibility rarely seen in curriculum design. When the Rutherford County Chamber of Commerce informed local CTE program director Tyra Pilgrim of a major shortage in medical lab technicians in the area, for instance, Pilgrim adjusted the county’s CTE offerings to start meeting the need. The chamber of commerce also worked with a local community college to start a medical lab technician program.

In Lenoir City, it makes sense to learn skills that are needed in the tourism industry, since one of the nation’s biggest tourist destinations is just 40 miles away. As the group of five young chefs puts the final touches on the holiday-cookie order, they’re doing so with the knowledge that the skills they’re developing in this kitchen are vastly improving their promise of future employment.

On January 11, 2017, the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO) and JPMorgan Chase announced nearly $20 million for ten U.S. states to dramatically increase the number of students who graduate from high school prepared for careers. Developed as part of our $75 million global New Skills for Youth initiative, each winning state will work with government, business and education leaders to strengthen career education and create pathways to economic success. Delaware, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nevada, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee and Wisconsin will each receive $1.95 million over three years to expand and improve career pathways for all high school students.

Read more about the skills gap.